1 Department of Management Studies, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

This study investigates the cronyism evidence in Indian listed firms and examines if excessive CEO and directors compensation reflect pay reciprocity impacting firm performance. Further the impact of CEO’s ties with the controlling owner on excess compensation, pay reciprocity and cronyism is also examined. OLS fixed effects regression on NSE 500 firms during 2002–2020 has been used for investigating the evidence of cronyism and the impact of CEOs’ ties with the controlling owner on cronyism. Based on the analysis it is observed that CEO compensation is strongly linked to CEO characteristics and corporate governance in addition to economic determinants. Consistent with reciprocity norms, we report a positive relationship between excess CEO compensation and excess director compensation, especially in firms where the CEO has ties to the controlling owner. However, pay reciprocity does benefit shareholders by improving subsequent firm value. Our findings indicate that excess CEO compensation increases subsequent firm value, especially in firms where the CEO has ties to the controlling owner.

CEO excess compensation, pay reciprocity, rent extraction, cronyism

Introduction

Excessive compensation for CEOs is one of the most widely discussed and debated topics among academics and corporate analysts (Core et al., 1999). Not surprisingly, these high compensation packages have attracted intense scrutiny both by media and statutory bodies, resulting in mandatory disclosure requirements. The general purpose of the board of directors (non-chair and non-executive) is to advise and monitor the CEO, set CEO compensation, and protect shareholders’ interests. However, in practice, the board may not effectively monitor the CEO’s actions, particularly in firms where the CEO has ties to the controlling owner (hereafter, owner-CEO) and/or outside directors have friendly relations with the CEO. Further, CEOs have considerable influence over the board of directors as they have little incentive to perform. As a result of this, the board of directors tend to develop a culture that discourages constructive criticism and creates an informational asymmetry between management and the board. Such issues may result in pay reciprocity between CEOs and outside directors, as a well-paid board is less likely to monitor the CEO compensation (Chen et al., 2019). Further, excessive compensation resulting from pay reciprocity may lead to poor future firm performance, referred to as cronyism (Brick et al., 2006).

Cronyism, a mutually benefiting phenomenon linked to excessive compensation and inadequate monitoring, has been studied in Australia (Chalmers et al., 2006), New Zealand (Li & Roberts, 2017), Taiwan (Chung et al., 2015), United Kingdom (Chen et al., 2019) and United States (Brick et al., 2006). The findings have been similar across countries with a positive relationship between the CEO’s excess compensation and outside directors’ excess compensation, confirming pay reciprocity. Further, studies have found (Brick et al., 2006; Chalmers et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2019; Chung et al., 2015) consistent evidence that excessive compensation due to reciprocity is associated with poor future firm performance, with an exception of New Zealand where a negative relationship was observed only for companies where the CEO is a board member.

The common feature of large Indian firms are; concentrated controlling ownership (Moolchandani & Kar, 2021), business group affiliation (Ghemawat & Khanna, 1996; Tomar & Korla, 2011), and owner-CEOs (Jaiswall & Firth, 2009). The controlling owners are often involved in the firm’s management as CEOs and directors. Owner-CEOs have considerable power in appointing outside directors on board (Ramaswamy et al., 2000), who, in turn, are responsible for setting the CEO’s compensation. Indian firms often make mutually acceptable appointments, that is, direct interlocking directorates, by trading one ‘outsider’ for another (Ghemawat & Khanna, 1996). These family connections, friendship, and social connectedness mean that outside directors will be swayed by the notion of reciprocity and have incentives to support mutual pay increases if reciprocity dynamics contribute to increases in their own compensation. Prior studies on CEO compensation in India revealed a failure of corporate governance resulting from outside directors’ unwillingness and inefficiency in determining CEO compensation at arms’ length. These pieces of evidence point to a board culture where outside directors are rewarded for failing to meet their obligations to minority shareholders. While anecdotal evidence suggests that outside directors’ compensation is positively associated with CEO compensation in India (Ghemawat & Khanna, 1996), there is no empirical evidence on how owner-CEOs influence CEO and directors’ pay reciprocity and, more importantly, how this pay reciprocity impacts subsequent firm performance, referred to as cronyism.

This study is a step further to the prior studies in the context of evidence of cronyism in an emerging market context with varying institutional and governance features. Indian context is ideal for examining the evidence of cronyism in an emerging market context due to its weak governance and distinct institutional environment. This study is divided into two parts. First, the relationship between excess CEO compensation and excess director compensation is analysed, particularly the impact of owner-CEO on CEO and directors’ pay reciprocity. Second, the impact of excessive CEO compensation due to reciprocity on subsequent firm performance is examined. We also analyse the owner-CEO impact on the relationship between excess compensation and subsequent firm performance. A sample of 6,790 firm-year observations from 2002 to 2020 is used for the analysis. Data is collected from 2002 since compensation disclosure became mandatory after 2001, resulting in a broader sample representing Indian firms. Methodology proposed by Core and Guay (2010) is used to determine excess compensation and Brick et al.’s (2006) methodology to examine pay reciprocity and owner-CEO’s impact on reciprocity. An improvised model of Chen et al.’s (2019) approach is adopted to examine Cronyism and owner-CEO’s impact on cronyism to assess if excess CEO compensation reflecting pay reciprocity leads to rent extraction, referred to as cronyism.

Firstly, CEO compensation using CEO attributes, corporate governance variables, and economic determinants is modelled. The study’s findings indicate that CEOs’ attributes influence their compensation; that is, CEO compensation is higher when the CEO is chairman, has a long career, and has ties with the controlling owner. Further, ownership structure and board composition influence their compensation; that is, CEOs receive higher compensation where the majority shareholder owns a significant amount of stock, the boards are smaller in size, and more outside directors are on board. The results indicate that CEOs are paid less in risky firms and firms with a higher proportion of tangible assets, as these assets serve as a monitoring mechanism. The study’s findings differ from previous Indian studies on CEO attributes’ role and corporate governance on CEO compensation.

Secondly, the relationship between excess CEO and excess director compensation, referred to as pay reciprocity, as well as the impact of owner-CEO on pay reciprocity is examined. Results indicate that Indian CEOs command excess compensation, which is positively related to directors’ excess compensation and vice-versa, indicating excessive managerial control and weak corporate governance. Further, it is observed that pay reciprocity strengthens in owner-CEO-managed firms, indicating that owner-CEOs can command excessive compensation and directors are unwilling to fulfil their obligations to minority shareholders.

Finally, to assess whether pay reciprocity is due to unobserved firm complexity or cronyism, the impact of excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity on subsequent firm performance is examined. The study’s findings suggest that excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity positively impacts subsequent market firm performance and negatively impacts accounting firm performance.; however, the accounting performance coefficient is weakly related. These results contrast with Brick et al.’s (2006) cronyism hypothesis. Further, it is observed that the impact of excess CEO compensation on firm performance strengthens in owner-CEO-managed firms indicating that controlling owners’ interest is in building empires and leaving a legacy for their future generations.

Literature is limited in the context of evidence of cronyism in the emerging market context and this could possibly be one of the initial studies, specifically the impact of the owner-CEO on pay reciprocity and rent extraction in large Indian firms. Analysis reveals evidence of cronyism indicating that excessive CEO compensation in Indian companies does not harm minority shareholder interests. On the contrary, efficient contracting evidence is observed suggesting that excess compensation motivates managers to increase the firm value, as their wealth is linked to the firm as controlling owners. The study concludes that CEO compensation in India reflects efficient contracting due to their controlling ownership and their motivation for increasing long-term firm value rather than short-term performance.

This document is structured as follows: the second section of the article presents a literature review and development of hypotheses; the third section describes the research methodology, empirical model, and descriptive statistics; the fourth section details the empirical results and their interpretation; and the fifth section offers the conclusions and limitations of the research.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

This section provides a theoretical background on CEO compensation’s level and structure, Indian institutional environment, pay reciprocity, and rent extraction, leading to hypotheses development.

CEO Compensation

Agency theorists have long believed that equity-based compensation structures align the executives’ interests with shareholders (Jensen & Murphy, 1990). Equity-based compensation typically rewards managers when they successfully meet future firm performance criteria (Baysinger & Hoskisson, 1990). Several studies have found a positive link between compensation and firm performance, that is, CEO compensation is linked to stock returns in Australia (Chalmers et al., 2006), China (Kato & Long, 2006), Japan (Basu et al., 2007), United States (Mehran, 1995), and South Korea (Choi et al., 2019). In India, however, stock returns are rarely used as a measure of firm performance due to relatively low stock market liquidity, uncertain foreign money flows, and high stock volatility, resulting in limited use of equity-based compensation (Balasubramanian et al., 2010; Jaiswall & Raman, 2019). Instead, several studies (Ghosh, 2003; Parthasarathy et al., 2006; Raithatha & Komera, 2016) in India have observed a positive relationship between CEO compensation and firm performance using an accounting measure (return on assets).

Studies (Baker et al., 1988; Ciscel & Carroll, 1980; Jaiswall & Firth, 2009; Tomar & Korla, 2011) have documented that CEOs in large companies have more responsibilities and are accountable for a large hierarchy, and they are motivated to increase their corporate power, control, and perks by expanding their size, so they are paid more in large companies. Evidence suggests that large firms pay more regardless of the measures used, either total assets (Finkelstein & Hambrick, 1989) or sales revenue (Lambert et al., 1993). In the United States (Core et al., 1999), United Kingdom (Chen et al., 2019), and India (Jaiswall & Firth, 2009), among other countries, CEO compensation is based on the company’s ability to expand. Although there is empirical evidence that growth opportunities are an important compensation metric, growth opportunities are frequently used as a control rather than a test variable in CEO compensation studies in the United States (Brockman et al., 2016; Grinstein & Hribar, 2004) and India (Jaiswall & Raman, 2019; Jaiswall et al., 2016). According to Core et al. (1999) and Cyert et al. (1997), the greater the market uncertainty, the greater the CEO risk, and the higher the CEO compensation in the US. In contrast, Jaiswall and Raman (2019) and Jaiswall et al. (2016) indicate that total CEO compensation is negatively related to a firm’s risk, implying that risk-taking is discouraged in Indian businesses. Further, Himmelberg et al. (1999) argued that since tangible assets are easier to monitor, companies with more tangible assets can have lower agency costs.

Studies have also documented the role of CEOs’ attributes on compensation level and structure. CEO duality is seen as a symbol of weak corporate governance, leading to excessive pay (Core et al., 1999). Ghosh (2006), Ramaswamy et al. (2000), and Tomar and Korla (2011) found a positive association between duality and CEO compensation in India, whereas Patnaik and Suar (2020) found a negative relationship, and Parthasarathy et al. (2006) did not find any. Longer Tenure increases CEO power, resulting in CEO entrenchment, which, in turn, positively influences their compensation (Chung & Pruitt, 1994; Dah & Frye, 2017). In India, CEOs with a longer tenure receive a higher compensation (Ghosh, 2006; Jaiswall et al., 2016). Bebchuk et al. (2011) and Choe et al. (2014) argued that owner-CEOs prefer compensation packages consisting mainly of cash than equity-based restricted stock. However, the empirical evidence on the compensation of the owner-CEO is mixed. McConaughy (2000) and Gomez-Mejia et al. (2003) found that, in the United States, owner-CEOs receive lower overall compensation and, in particular, incentive-based compensation than non-owner-CEOs. In contrast, according to Cohen and Lauterbach (2008), owner-CEOs in Israeli companies earn significantly more compensation (around 50%) than non-owner-CEOs. In Indian firms, Jaiswall et al. (2016) found that the owner-CEOs do not receive higher compensation. Ghosh (2006) argued that when the CEO has ties to the controlling owner, both CEO and board compensation increase simultaneously, implying that directors’ compensation setting process is reciprocal. However, pay reciprocity, the impact of owner-CEO on pay reciprocity and rent extraction in Indian firms, is still unknown.

Several studies (Core et al., 1999; Mehran, 1995) have examined ownership structures’ role in compensation and found that controlling and institutional shareholders closely monitor CEO compensation. However, the empirical evidence on whether ownership structures play a significant role in CEO compensation in Indian companies is mixed. Ramaswamy et al. (2000) find a negative relationship between CEO compensation and controlling ownership, whereas Chakrabarti et al. (2008) find a positive relationship, and Patnaik and Suar (2020) and Jaiswall et al. (2016) find none. In addition, Jaiswall et al. (2016) find a positive relationship between CEO compensation and institutional shareholders in Indian firms; Patnaik and Suar (2020) find a negative relationship, and Parthasarathy et al. (2006) find no relationship. Further, while Ghosh (2010) and Patnaik and Suar (2020) find evidence of higher compensation in business group-affiliated firms, Ghosh (2006) does not.

Several studies have commented on boards’ effectiveness, arguing that information asymmetry, lack of coordination among outside directors, and directors’ inability to negotiate CEO compensation at arm’s length results in increased CEO compensation because the divided board can not effectively monitor CEO compensation (Boyd, 1994; Core et al., 1999). However, empirical evidence on the boards’ effectiveness is mixed. Ghosh (2006) and Jaiswall et al. (2016) find no relationship between CEO compensation and board size, whereas Chakrabarti et al. (2012) find a positive relationship. Furthermore, Ghosh (2006) finds a positive relationship between CEO compensation and the proportion of independent directors, while Tomar and Korla (2011) find a negative relationship, and Jaiswall et al. (2016) find no relationship. However, the role of board composition in the context of pay reciprocity and rent extraction in Indian companies is still unknown.

The Indian Institutional Environment

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) was created in 1992 to monitor and regulate the securities market after the Indian government proposed a series of reforms in 1991 to gradually deregulate industries and open the economy to domestic and foreign private companies. Due to the opening of the economy, increased competition, and foreign capital, SEBI and the Indian government formed several committees to examine various corporate governance issues, and these committees outlined the importance of board composition, remuneration practices, separation of the chairman and CEO’s offices, and restricting the directorship for an individual. However, studies have claimed that enforcement has been lax despite strict investor protection laws and corporate governance rules, and companies are seldom penalised for breaching governance standards.

The domination of business group-affiliated firms, that is, a group of companies controlled by a family-owned holding company through direct-shareholding, cross-shareholding pyramidal ownership structure, is a central feature of the Indian corporate sector (La Porta et al., 1999; Narayanswamy et al., 2012; Moolchandani & Kar, 2021). In business group firms, family members are frequently involved in management, resulting in owner-managers at the organisation’s highest levels (Jackling & Johl, 2009). A business group affiliated firms’ CEOs are either family members or family members’ relatives. Unlike CEOs in the United States, Indian CEOs stay at companies for extended periods, often serving as both CEO and chairman (Jaiswall & Raman, 2019). Though Indian business groups tunnel profit (Bertrand et al., 2002), they help their affiliated firms smooth the distress periods through the internal fund, enabling them to outperform standalone firms (Khanna & Palepu, 2000). Concentrated controlling ownership is a common characteristic of Indian businesses, with families usually owning a significant majority of their equity shares. Jaiswall et al. (2016) reported that controlling shareholders own 52% of a company’s equity on average in three out of four Indian companies.

The CEO compensation is governed by Indian corporate law (see Narayana Murthy Committee on Corporate Governance 2003 recommendations), which gives the remuneration committee of a company’s board of directors (consisting of at least three non-executive directors) the authority to set it. The law requires businesses to disclose CEO compensation in their annual report, but they are not obligated to report the compensation determination process’s details. In Indian firms, the CEO’s compensation is summarised under major groups: salary, retirement benefits, bonuses, stock options, pension. However, Just about 15% of the top 500 Indian companies give their CEOs stock options, and the grants are usually small (Balasubramanian et al., 2010).

Pay Reciprocity and Owner-CEO

According to Gouldner (1960), the reciprocity norm implies that acts would be reciprocated in kind. Previous studies indicate that outside directors named by the CEO are swayed by indebtedness (Hermalin & Weisbach, 2001) and reciprocity notions in their decisions regarding CEO compensation (Main et al., 1995). Indian companies are affiliated with business groups (Raithatha & Komera, 2016) with concentrated controlling shareholding (Ghosh, 2006) and employ owner-CEO (Jaiswall et al., 2016). Owner-CEOs have considerable influence over their outside directors (Boivie et al., 2015), which they might use to influence their compensation-setting process, thereby securing excess compensation. Despite being appointed from outside the company, outside directors tend to have ties to the CEO and controlling owners in India and are less likely to use their power to monitor CEO compensation (Ramaswamy et al., 2000). Hence, outside directors and CEOs have incentives to support mutual compensation increases if reciprocity dynamics increase their own compensation.

Indian companies have concentrated ownership which is often majorly controlled by firms’ promoters, followed by institutional shareholders (Sarkar & Sarkar, 2000). Given immense wealth at stake, controlling owners would want to actively monitor and scrutinise management (Shleifer & Vishny, 1996); therefore, a CEO is appointed to that post primarily based on social connections and often has ties to the controlling owner. Similarly, outside directors are appointed by controlling owners. Although outside directors serve on the board, they are unlikely to monitor and control CEO compensation in the same way that outsider-dominated boards in the US and UK are known to do (Ramaswamy et al., 2000). We posit that outside directors being passive monitors are likely to support reciprocal compensation increase in a firm with owner-CEO, that is, excessive compensation for both CEO and outside directors. On the contrary, outside directors are likely to reduce CEO compensation and align it to the firm performance in a professionally managed firm, thereby reducing reciprocal compensation. We have the following hypotheses for the pay reciprocity and owner-CEO:

H1: There is no association between CEO excess compensation and directors excess compensation.

H2: There is no impact of owner-CEO on the association between CEO excess compensation and directors excess compensation.

Rent Extraction and Owner-CEO

The excessive CEO compensation, primarily due to reciprocity, indicates that compensation negotiations are more of a formality than a mechanism for deciding compensation package that shows outside director efforts to shareholders and rewards for managerial talent. Core et al. (1999) argued that excess CEO compensation might be consistent with either rent extraction or labour market demand. CEO’s excess compensation could mean higher equilibrium compensation for a talented CEO, reflecting efficient contracting (Core et al., 1999) or governance failure in compensation setting, reflecting rent extraction (Bebchuk et al., 2002; Core et al., 1999; Jaiswall & Firth, 2009). Li and Roberts (2017) argued that excess CEO compensation might encapsulate unobservable CEO efforts that are not obvious to outsiders, inducing more CEOs’ efforts leading to higher subsequent firm performance; on the contrary, excess compensation might be a sign of a board culture conducive to CEO collusion, resulting in poor subsequent firm performance.

Owner-CEOs in Indian family-controlled firms receive excess compensation, which might be due to rent extraction or efficient contracting. Choi et al. (2019) suggested that excessive compensation for owner-CEOs is justified in family-controlled business group firms because they have strong incentives to generate profits and maintain the firm’s financial well-being; they are also less likely to act against the company’s interests and are more likely to see excessive compensation as a way to motivate them, demonstrating efficient contracting. On the contrary, Brick et al. (2006) indicate that CEOs puts self-interest ahead of controlling shareholder interests and their excess compensation result in suboptimal performance. Thus, we posit that owner-CEO excess compensation would demonstrate efficient contracting, and non-owner-CEOs excess compensation would demonstrate rent. We have the following hypotheses for the rent extraction and owner-CEO:

H3: There is no association between excess CEO compensation and subsequent firm performance.

H4: There is no impact of owner-CEO on the association between excess CEO compensation and subsequent firm performance.

Methodology

In this section, the sample selection, measurement of the variables, and the methodology adopted are discussed. Descriptive statistics are also presented in this section.

Sample Selection

The companies forming NSE 500 Index has been used for empirical analysis in this study. The NIFTY 500 Index represents about 96.1% of the free-float market capitalisation of the stocks listed on NSE, and the study period was from 2002 to 2020. To ensure homogeneity of data financial services companies have been excluded from the sample. Data on compensation, ownership structure, firm performance, and corporate governance was collected from the CMIE Prowess database in line with Balasubramanian et al. (2010); Khanna and Palepu (2000) and Jaiswall et al. (2016). The final sample included 6790 firm-year observations, consisting of 397 firms with an average of 17 years each, and the final data set was an unbalanced panel. All variables have been winsorised at 1% level to mitigate the likelihood of outliers.

Econometric Model

OLS regression with firm and year fixed effects is applied to examine the pay reciprocity among CEO and directors. Core and Guay (2010) defined excess compensation as compensation that CEOs can command after controlling: CEO ability, CEO effort, and risk premiums. Thus, to estimate CEO_Residual and Director_Residual, Equation (1) is used to regress CEO (Director) cash and total compensation on economic determinants, CEO attributes, and corporate governance variables while controlling for year and firm fixed effects. CEO_Residual and Director_Residual is the prediction error in the dependent variable: the natural logarithm of total CEO and directors compensation, respectively.

(1)

(1)

To determine pay reciprocity (Hypothesis 1), in Equation (2), Director_Residual is used as an explanatory variable to look at the impact of outside directors’ excess compensation on the logarithm of total CEO compensation. Further, CEO_Residual is used to assess the CEO excess compensation’s impact on the natural logarithm of total director compensation.

(2)

(2)

To investigate the owner-CEO impact on pay reciprocity (Hypothesis 2), in Equation (3), the interactions of Director_Residual and CEO_Residual with owner-CEO as an explanatory variable is included. Firstly, Director_Residual*owner-CEO is used to examine the impact of excess director compensation on CEO compensation in owner-CEO-managed firms. Secondly, CEO_Residual*owner-CEO is included to examine the impact of excess CEO compensation on director compensation in owner-CEO-managed firms.

(3)

(3)

To investigate the relationship between excessive CEO compensation due to reciprocity and subsequent firm performance, CEO_DUE_TO_DIR is calculated as the difference between fitted CEO compensation with outside directors’ excess compensation and fitted CEO compensation without outside directors’ excess compensation. To test Hypothesis (3), in Equation (4), the relationship between CEO excess compensation and subsequent firm performance is examined using CEO_DUE_TO_DIRt–1 as an explanatory variable. Further three firm performance measures are used as dependent variables: ROA, Tobin’s Q, and TRS.

(4)

(4)

To investigate the impact of owner-CEO on the relationship between excessive CEO compensation due to reciprocity and subsequent firm performance (Hypothesis 4), in Equation (5), CEO_DUE_TO_DIRt–1*owner-CEOt–1 is used as an explanatory variable. Further three firm performance measures are used as dependent variables: ROA, Tobin’s Q, and TRS. The definition of the variables used in the study is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.Definitions of Variables Used in the Study

Source: The authors.

(5)

(5)

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for main explanatory variables, CEO and outside director compensation. CEOs received an average of 32.6 million INR in cash compensation and 39 million INR in total compensation across the sample period. Outside directors received cash compensation of 32.9 million INR and total compensation of 29.2 million INR on average. The CEO’s relative importance is measured by the percentage of total compensation paid to all board members that the CEO receives. On an average, CEOs receive at least 42% of the total compensation paid to all board members.

Table 2.Descriptive Statistics

Source: The authors.

Notes: Table 2 presents summary statistics for the main input variables.

Table 1 contains the definitions of the variables used in the study.

It is observed that the sample firms have an average return on assets of 8.2%, Tobin’s Q of 2.06 times, Alpha of 0.232%, and Asset Tangibility of 28.4% for economic determinants. Further, sample firms have an average net sale of 63.7 billion INR and total assets of 91.7 billion INR. The sample firms’ ownership structure has an average majority holding of 50.7% and an institutional holding of 18.4%. It may also be noted that 57% of the sample firms are affiliated with a family-controlled business group. In terms of board composition, it is found that sample firms have nine board members, six of whom are non-executive directors; additionally, three board members have ties to the controlling family on average. Four out of six outside directors are busy directors in the sample firms, meaning they have three other directorships on average (Sarkar & Sarkar, 2009).

Empirical Results

Determinants of CEO and Outside Directors Compensation

Table 3 reports the OLS regression estimates on CEO and outside director compensation. In addition to reporting CEO cash and total compensation results, results for the outside directors’ cash and total compensation is also reported. CEO (Director) compensation is modelled in line with Core and Guay (2010), including firm and year fixed effects, by controlling efforts, ability, and risk premium proxies. Table 3 presents the estimated results in Columns (1) through (4).

Table 3.CEO and Director Compensation

Source: The authors.

Notes: Table 3 reports the CEO and outside director compensation regressions result using an OLS regression with year and firm fixed effects. The models are estimated using the natural log in CEO cash and total compensation and the natural log in director cash and total compensation.

Table 1 contains the definitions of the variables used in the study. Standard errors are in parenthesis.

***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .1.

Consistent with prior studies, it is observed that CEO’s total compensation is positively related to ROA, size, duality, owner-CEO, tenure, institutional holding, the proportion of non-executive directors, and negatively related to asset tangibility, business group affiliation, board size, and the proportion of owner-executives on board. However, CEO compensation is not associated with firm risk and majority holding, and the proportion of owner-executives on the board. Further, it is observed that outside directors’ total compensation is positively associated with ROA, firm size, firm risk, owner-CEO, institutional holding, majority holding, board size, the proportion of non-executive directors on the board, and the proportion of owner-executives on the board whereas negatively associated with asset tangibility and CEO duality, which is consistent with prior research. However, there was no significant association of directors compensation with CEO tenure and business group affiliation.

Consistent with Raithatha and Komera (2016), the coefficients of ROA are positive and significant for CEO (Director) compensation implying a pay-performance link in managerial compensation contracts. Firm size is positively associated with CEO (Director) compensation, suggesting that larger firms demand higher quality executives and pay for such quality (Chung & Pruitt, 1996; Cyert et al., 2002; Jaiswall et al., 2016). Firm risk is positively associated CEO (Director) compensation, in contrast to Jaiswall and Firth (2009). However, the relationship is only significant for directors’ compensation, implying an incentive for the outside director to assume additional risk. The asset tangibility is negatively related to CEO (Director) compensation, implying that businesses with more tangible assets will have lower agency costs as tangible assets act as a monitoring mechanism and are easier to track (Himmelberg et al., 1999).

Further, the coefficients of three variables of the CEO’s attributes, namely owner-CEO, CEO duality, and tenure are reported in Table 3. The owner-CEO and the CEO’s tenure positively impact CEO (director) compensation, implying a strong bond between the CEO and the outside directors due to a long-term relationship and a weak governance environment. However, the coefficient of a CEO’s tenure is not significant for directors’ total compensation. Consistent with Tomar and Korla (2011), it is observed that CEO duality is positively associated with their compensation but negatively associated with director’s compensation (Saravanan et al., 2016) implying that dual CEOs are more likely to be entrenched and have more influence over the board, decreasing the effectiveness of directors’ monitoring. However, the results contrast with Parthasarathy et al. (2006) and Jaiswall et al. (2016), who did not find any relationship between duality and compensation.

Table 3 also reports the coefficients for three ownership variables and three board composition variables. The majority and institutional holdings have a positive impact on CEO (Director) compensation; however, the relationship is not significant in Models (2) and (3). The study’s findings contradict Jaiswall et al. (2016) and Jaiswall and Firth (2009), who found no link between majority ownership and CEO compensation. Consistent with Ghosh (2006), it is observed that business-group affiliated firms limit CEO (director) compensation. Board size coefficients are negatively associated with CEO compensation and positively associated with directors compensation implying monitoring efficiency of board members in limiting CEO compensation. The findings contradict those of Chakrabarti et al. (2012), who found a positive relationship between CEO compensation and board size. The proportion of non-executive directors is positively associated with CEO (director) compensation; however, Tomar and Korla (2011) find a negative relationship; Jaiswall et al. (2016) found no link; Ghosh (2006) found a positive link, which is consistent with our findings. Finally, the proportion of owner-executives is negatively associated with CEO compensation and positively associated with director’s compensation, suggesting that when they are not the firm’s CEO, owner-executives are overpaid. However, the coefficients are not significant for CEO compensation.

Pay Reciprocity

OLS fixed effects estimator regression results on CEO and director pay reciprocity are presented in Table 4. The reciprocity between CEO and outside director compensation is examined by including Director_Residual and CEO_Residual as additional explanatory variables in Models (1) and (3). To examine the impact of owner-CEO on pay reciprocity, interaction terms Director_Residual*owner-CEO and CEO_Residual*owner-CEO in Models (2) and (4) are included. Table 4 summarises the findings on CEO and director pay reciprocity and owner-CEO’s impact on pay reciprocity.

Table 4.CEO and Director Pay Reciprocity

Source: The authors.

Notes: Table 4 provides regression results on CEO and outside directors’ pay reciprocity and owner-CEO’s impact on pay reciprocity after controlling for standard determinants. The estimations use an OLS regression with year and firm fixed effects.

Table 1 contains the definitions of the variables used in the study. Standard errors are in parenthesis.

***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .1.

In Table 4, the estimated coefficients on Director_Residual (0.190, t–statistic 0.012) and CEO_Residual (0.272, t–statistic 0.017) are found to be significantly positive; therefore, Hypothesis 1 is rejected, implying pay reciprocity in CEO and outside directors compensation. These results are consistent with the findings of Brick et al. (2006), Chen et al. (2019) and Li and Roberts (2017). In Table 4 Model (1), the coefficient of Director_Residual is (0.190, t–statistic 0.012), that can be interpreted as elasticity because both compensation variables are in logarithmic form, that is, a 10% increase in Director_Residual is associated with a 19.03% increase in CEO total compensation. Similarly, the CEO_Residual coefficient (0.272, t–statistic 0.017) indicates that a 10% increase in CEO_Residual is associated with a 27.2% increase in directors’ total compensation. In terms of economic significance, a 10% rise in outside directors’ excess compensation will lead to an increase in CEO total compensation of approximately 7.42 million INR on average, based on the average compensation levels presented in Table 2. Similarly, a 10% rise in CEO excess compensation will increase total compensation for outside directors by approximately 7.94 million INR on average.

Owner-CEOs’ impact on pay reciprocity between CEOs and directors is also investigated, because 56% of CEOs in sample firms have ties to the controlling owner. To determine the owner-CEO impact on pay reciprocity, the models estimated in Columns (2) and (4) include interaction terms, Director_Residual*Owner-CEO, and CEO_Residual*Owner-CEO, respectively. The coefficients for Director_Residual*Owner-CEO (0.198, t–statistic 0.024) and CEO_Residual*Owner-CEO (0.216, t–statistic 0.036) indicate pay reciprocity in owner-CEO-managed firms, implying that pay reciprocity among CEO and outside directors strengthens in firms where CEOs have ties to the controlling owner. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is rejected.

Rent Extraction

Berry et al. (2006) argued that CEO and directors’ pay reciprocity could exist if the firm has a large hierarchy and complex operations, which requires both CEO and directors’ skill and efforts. However, for the cronyism hypothesis to be true, excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity must result in poor subsequent firm performance (Brick et al., 2006). This section investigates whether excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity results in subsequent poor firm performance, referred to as cronyism. The relationship between excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity (CEO_DUE_TO_DIR) and one-year ahead ROA, one-year ahead Tobin’s Q, and one-year ahead TRS is also examined using an improved version of Chen et al.’s (2019) model. The interaction term, CEO_DUE_TO_DIR*Owner-CEO, to measure owner-CEO’s impact on the relationship between excess CEO compensation and subsequent firm performance is examined. Tables 5 summarises the evidence of cronyism in sample firms. All the models include firm and year fixed effects.

Table 5.CEO Rent Extraction

Source: The authors.

Notes: Table 5, in Models (1)–(3), reports the impact of excess CEO compensation due to pay reciprocity on subsequent firm performance after controlling for other standard determinants, and, in Models (4)–(6), reports the impact of Owner-CEO on the relationship between excess CEO compensation due to pay reciprocity on subsequent firm performance after controlling for other standard determinants. The estimations use an OLS regression with year and firm fixed effects.

Table 1 contains the definitions of the variables used in the study. Standard errors are in parenthesis.

***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .1.

In Table 5, CPS, owner-CEO, firm growth, and firm risk are controlled. CPS, owner-CEO, growth, and firm risk positively influence firms’ ROA; however, the relationship is only significant for owner-CEO and firms’ growth. Further, CPS, owner-CEO, and Growth positively influence both market performance measures, whereas beta negatively influences both. However, the relationship is only significant for firms’ growth and risk. In Columns (2) and (3) of Table 5, the firm risk is negatively related to future firm performance, implying that a firm’s stock volatility will result in a firm’s lower subsequent market performance. Owner-CEO and CPS’s coefficients indicate that CEOs’ ties to the controlling owner and their pay slice positively influence accounting performance whereas negatively influence market performance.

In Table 5, Columns (1)–(3) reports the coefficient of CEO_DUE_TO_DIR, that is negatively related to ROA, positively related to Tobin’s Q and TRS; however, the relationship is not significant for TRS. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is rejected, implying that excessive CEO compensation leads to poor accounting firm performance but improved market performance. The study findings are in contrast to Chen et al. (2019), who found a negative relationship between industry-adjusted Tobin’s Q and CEO excess compensation due to directors in the UK.

Further, the impact of owner-CEO on the relationship between CEO excess compensation and subsequent firm performance is examined because most CEOs in sample firms have ties to the controlling owner. Interaction variable, CEO DUE TO DIR*Owner-CEO, is used to examine owner-CEO’s impact on the relationship between CEO excess compensation and subsequent firm performance. In Table 5, the CEO DUE TO DIR*Owner-CEO coefficients in Columns (4)–(6) show a significant positive relationship between ROA, Tobin’s Q, and TRS. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is rejected, implying that the excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity will correspond to better performance in the future for owner-CEO-managed companies. In Column (4), the interaction variable’s coefficient is significantly positive, indicating excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity results in improved accounting performance of owner-CEO-managed companies; however, economic significance is minuscule. Similarly, coefficients in Models (5) and (6) indicate that, in owner-CEO-managed companies, a 1% increase in excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity results in increased market performance, that is, 0.0084 times in Tobin’s Q and 0.0014% above the market return, respectively.

Conclusion

This study tests the validity of the cronyism hypothesis in an emerging market context using a sample of listed Indian firms. It is believed that CEOs’ and directors’ excess compensation due to reciprocity harms shareholder value. Further, the impact of CEOs’ ties with controlling owners on cronyism is also examined. Unlike prior studies, which suffer from omitted variable bias, small sample, and limited generalisability, CEO compensation is modelled using a 19 years sample period and employing Core and Guay’s (2010) theoretical framework and methodology. It is observed that economic determinants, CEO attributes, and corporate governance variables are significant drivers of CEO and director compensation in India. The study’s findings indicate that CEOs receive higher compensation in firms where the CEO is also chairman of the board, has a longer tenure, and ties to the controlling owner. Further, CEOs are paid more in companies with a high level of controlling ownership, small board of directors, and a large number of outside directors.

Since most Indian firms are closely held, the CEOs have ties to the controlling owner and have an essential role in outside directors’ appointments; owner-CEOs are more likely to be entrenched and command excess compensation. The study presents that the owner-CEOs receive higher compensation in Indian firms, but their presence in the company and their excess compensation due to reciprocity do not result in poor subsequent firm performance. Therefore, it can be indicated that there is no consistent and robust evidence favouring the cronyism hypothesis in India. This study is conducted in two parts. Firstly, the study provides evidence of CEO and directors’ pay reciprocity, especially in firms with owner-CEO. Our findings show a positive relationship between CEO and outside director excess compensation, with owner-CEOs commanding higher compensation due to pay reciprocity. Secondly, to prove the cronyism hypothesis, the relationship between excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity and subsequent firm performance is also examined. In contrast with Brick et al. (2006), Chen et al. (2019), and Li and Roberts (2017), excess CEO compensation is assessed based on reciprocity norms, increases a firm’s accounting and market-based performance, especially in firms with owner-CEOs. The findings suggest that excess CEO compensation due to reciprocity does not decrease future performance but instead increases firm value.

The study adds to the CEO compensation and corporate governance literature in an emerging market context. However, there are a few limitations to this study. Firstly, data from a single country is used to investigate the evidence of cronyism in emerging economies. Despite the fact that owner-CEOs are a common occurrence in emerging economies, ownership structures in these economies differ significantly from country to country, and as a result, the findings may not be generalisable to other governance environments in emerging market contexts. Secondly, CEOs’ influence by their ties to the controlling owner is examined; while the findings are consistent with other emerging economies, CEOs’ influence may vary depending on a firm’s affiliation with a business group and the majority shareholder’s concentration. Future studies could include business group affiliation and majority shareholder concentration to understand better the owner-CEOs’ influence on their compensation level and subsequent firm performance. Finally, this sample only includes large publicly traded companies; the findings for smaller companies can vary.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors are thankful to IIT Madras for supporting this research.

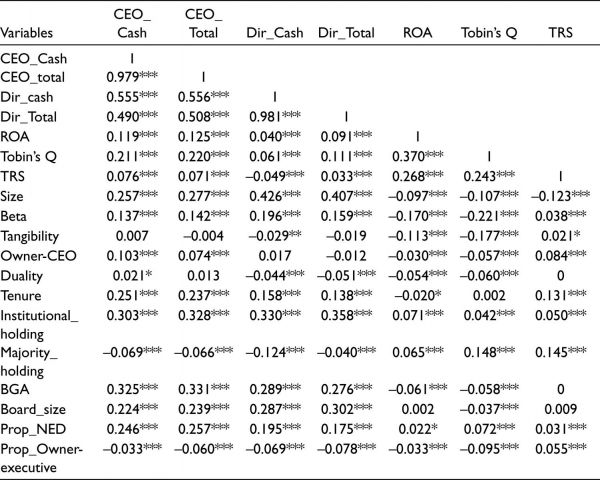

Appendix A.The correlation coefficients for the main explanatory variables and dependent variables. The correlations are relatively low, with the most significant being 0.328 between CEO total compensation and institutional holding, indicating no multicollinearity problem.

Source: The authors.

Angelis, D. De., & Grinstein, Y. (2015). Performance terms in CEO compensation contracts. Review of Finance, 19(2), 619–651. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfu014

Baker, G. P., Jensen, M. C., & Murphy, K. J. (1988). Compensation and Incentives: Practice vs. Theory. The Journal of Finance, 43(3), 593–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1988.tb04593.x

Balasubramanian, N., Black, B. S., & Khanna, V. (2010). The relation between firm-level corporate governance and market value: A case study of India. Emerging Markets Review, 11(4), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2010.05.001

Basu, S., Hwang, L. S., Mitsudome, T., & Weintrop, J. (2007). Corporate governance, top executive compensation and firm performance in Japan. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 15(1), 56–79.

Baysinger, B., & Hoskisson, R. E. (1990). The Composition of Boards of Directors and Strategic Control: Effects on Corporate Strategy. Academy of Management Review, 15(1), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1990.4308231

Bebchuk, L. A., Cremers, K. M., & Peyer, U. C. (2011). The CEO pay slice. Journal of financial Economics, 102(1), 199–221.

Bebchuk, L. A., Fried, J., & Walker, D. (2002). Managerial power and rent extraction in the design of executive compensation.

Berry, T. K., Fields, L. P., & Wilkins, M. S. (2006). The interaction among multiple governance mechanisms in young newly public firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(3), 449–466.

Bertrand, M., Mehta, P., & Mullainathan, S. (2002). Ferreting out tunneling: An application to Indian business groups. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355302753399463

Boivie, S., Bednar, M. K., & Barker, S. B. (2015). Social Comparison and Reciprocity in Director Compensation. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1578–1603. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312460680

Boyd, B. K. (1994). Board Control and CEO compensation. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 335–344.

Brick, I. E., Palmon, O., & Wald, J. K. (2006). CEO compensation, director compensation, and firm performance: Evidence of cronyism?. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2005.08.005

Brockman, P., Lee, H. S. G., & Salas, J. M. (2016). Determinants of CEO compensation: Generalist-specialist versus insider-outsider attributes. Journal of Corporate Finance, 39, 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.04.007

Chakrabarti, R., Subramanian, K., Yadav, P. K., & Yadav, Y. (2012). 21 Executive compensation in India. In Research handbook on executive pay (p. 435).

Chakrabarti, R., Megginson, W., & Yadav, P. K. (2008). Corporate Governance in India. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 17(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9173-6

Chalmers, K., Koh, P. S., & Stapledon, G. (2006). The determinants of CEO compensation: Rent extraction or labour demand?. British Accounting Review, 38(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2006.01.003

Chen, J. Goergen, M., Leung, W. S., & Song, W. (2019). CEO and director compensation, CEO turnover and institutional investors: Is there cronyism in the UK?. Journal of Banking and Finance, 103, 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2019.03.019

Choe, C., Tian, G. Y., & Yin, X. (2014). CEO power and the structure of CEO pay. International Review of Financial Analysis, 35, 237–248.

Choi, W., Lee, E., & Leach-López, M. A. (2019). Excess Compensation and Corporate Governance. Korea International Accounting Review, 86(8), 165–188. https://doi.org/10.21073/kiar.2019..86.008

Chung, H., Judge, W. Q., & Li, Y. H. (2015). Voluntary disclosure, excess executive compensation and firm value. Journal of Corporate Finance 32, 64–90.

Chung, K. H., & Pruitt, S. W. (1996). Executive ownership, corporate value, and executive compensation: A unifying framework. Journal of Banking and Finance, 20(7), 1135–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(95)00039-9

Chung, K. H., & Pruitt, S. W. (1994). A simple approximation of Tobin’s q. Financial management, 70–74.

Ciscel, D. H., & Carroll, T. M. (1980). The Determinants of Executive Salaries: An Econometric Survey. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 62(1), p. 7. https://doi.org/10.2307/1924267

Cohen, S., & Lauterbach, B. (2008). Differences in pay between owner and non-owner CEOs: Evidence from Israel. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 18(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mulfin.2007.02.005

Core, J. E., & Guay, W. R. (2010). Is CEO Pay Too High and Are Incentives Too Low? A Wealth-Based Contracting Framework. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.24.1.5

Core, J. E., Holthausen, R. W., & Larcker, D. F. (1999). Corporate governance, chief executive officer compensation, and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 51(2), 371–406. https://doi.org/10.2307/257098

Cyert, R. M., Kang, S. H., & Kumar, P. (2002). Corporate governance, takeovers, and top-management compensation: Theory and evidence. Management Science, 48(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.48.4.453.205

Dah, M. A., & Frye, M. B. (2017). Is board compensation excessive?. Journal of Corporate Finance, 45, 566–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.06.001

Finkelstein, S., & Hambrick, D. C. (1989). Chief Executive Compensation: A Study Of Markets and Potical Process. Strategic Management Journal, 10(2), 121–134

Ghemawat, P., & Khanna, T. (1998). The nature of diversified business groups: A research design and two case studies. Journal of Industrial Economics, 46(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6451.00060

Ghemawat, P., & Khanna, T. (1996). The future of India’s business groups: An analytical perspective. In Academy of Management National Meetings. Cincinnati, OH. Guillén, MF (2000). Business Groups in Emerging Economies: A Resource-Based View. The Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 362–380.

Ghosh, A. (2003). Board structure, executive compensation and firm performance in emerging economies: Evidence from India.

Ghosh, A. (2006). Determination of executive compensation in an emerging economy: Evidence from India. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 42(3), 66–90. https://doi.org/10.2753/REE1540-496X420304

Ghosh, S. (2010). Firm Performance and CEO Pay: Evidence from Indian Manufacturing. Journal of Entrepreneurship, 19(2), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/09713557 1001900203

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Larraza-Kintana, M., & Makri, M. (2003). The Determinants of Executive Compensation in Family-Controlled Public Corporations. Academy of Management Journal, 46(2), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.5465/30040616

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. American Sociological Review, 25(4), 161–178.

Grinstein, Y., & Hribar, P. (2004). CEO compensation and incentives: Evidence from M&A bonuses. Journal of Financial Economics, 73(1), 119–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2003.06.002

Hermalin, B. E., & Weisbach, M. S. (2001). Boards of Directors as an Endogenously Determined Institution: A review of the Economic Literature. National Bureau of Economic Research, 3.

Himmelberg, C. P., Hubbard, G. R., & Palia, D. (1999). Understanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 53(3), 353–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(01)00085-X

Jackling, B., & Johl, S. (2009). Board structure and firm performance: Evidence from India’s top companies. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(4), 492–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00760.x

Jaiswall, M., & Firth, M. (2009). CEO pay, firm performance, and corporate governance in India’s listed firms. International Journal of Corporate Governance, 1(3), p. 227. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijcg.2009.029367

Jaiswall, S. S., & Raman, K. K. (2019). Sales Growth, CEO Pay, and Corporate Governance in India. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X19825672

Jaiswall, S. S. K., & Bhattacharyya, A. K. (2016). Corporate governance and CEO compensation in Indian firms. Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics, 12(2), 159–175.

Jensen, C. M., & Murphy, J. K. (1990). Performance Pay and Top-Management Incentives. Journal of Political Economy, 98(2), 225–264. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2937665

Joe Ueng, C., Wells, D. W., & Lilly, J. D. (2000). CEO influence and executive compensation: Large firms vs. small firms. Managerial Finance, 26(8), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074350010766800

Kato, T., & Long, C. (2006). CEO turnover, firm performance, and enterprise reform in China: Evidence from micro data. Journal of Comparative Economics, 34(4), 796–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2006.08.002

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (2000). Is group affiliation profitable in emerging markets? an analysis of diversified Indian business groups. Journal of Finance, 55(2), 867–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00229

La Porta, R., Johnson, S., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Tunnelling. [NBER Working Paper No. 7523, pp. 124–141]. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814439367_ 0005

Lambert, R. A., Larcker, D. F., & Weigelt, K. (1993). The Structure of Organizational Incentives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38(3), 438–461. https://www.jstor. org/stable/2393375

Li, M., & Roberts, H. (2017). Director and CEO pay reciprocity and CEO board membership. Journal of Economics and Business, 94, 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2017.10.002

Main, B. G. M., O’reilly, C. A., & Wade, J. (1995). The CEO, the board of directors and executive compensation: Economic and psychological perspectives. Industrial and Corporate Change, 4(2), 293–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/4.2.293

McConaughy, D. L. (2000). Family CEOs vs. Nonfamily CEOs in the Family-Controlled Firm: An Examination of the Level and Sensitivity of Pay to Performance. Family Business Review, 13(2), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2000.00121.x

Mehran, H. (1995). Executive compensation structure, ownership, and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 38(2), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(94)00809-F

Moolchandani, R., & Kar, S. (2021). Family control, agency conflicts, corporate cash holdings and firm value. International Journal of Emerging Markets.

Narayanaswamy, R., Raghunandan, K., & Rama, D. V. (2012). Corporate governance in the Indian context. Accounting Horizons, 26(3), 583–599. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-50179

Parthasarathy, A., Bhattacherjee, D., & Menon, K. (2006). Executive Compensation, Firm Performance and Corporate Governance: An Empirical Analysis. Economic & Political Weekly, 41(39), 4139–4147. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.881730

Patnaik, P., & Suar, D. (2020). Does corporate governance affect CEO compensation in Indian manufacturing firms?. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2115

Raithatha, M., & Komera, S. (2016). Executive compensation and firm performance: Evidence from Indian firms. IIMB Management Review, 28(3), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2016.07.002

Ramaswamy, K., Veliyath, R., & Gomes, L. (2000). A study of the determinants of CEO Compensation in India. Management International Review, 40(2), 167–191. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40835875

Saravanan, P., Avabruth, S. M., & Srikanth, M. (2016). Executive compensation, corporate governance and firm performance: Evidence from India. International Journal of Corporate Governance, 7(4), p. 377. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijcg.2016.10003330

Sarkar, J., & Sarkar, S. (2000). Large Shareholder Activism in Corporate Governance in Developing Countries: Evidence from India. International Review of Finance, 1(3), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2443.00010

Sarkar, J., & Sarkar, S. (2009). Multiple board appointments and firm performance in emerging economies: Evidence from India. Pacific Basin Finance Journal, 17(2), 271–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2008.02.002

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1996). A Survey of Corporate Governance. National Bureau of Economic Research, 59–92.

Tomar, A., & Korla, S. (2011). Global-Recession-and-Determinants-of-CEO. Advances In Management, 3(2), 11–26.